Luxury in the 21st century has become increasingly homogenised. From London to Tokyo, the “five-star experience” often looks like a sterile blend of glass, steel, and neutral linens. But in Southeast Asia, a different kind of luxury survives – one that’s built on the soul of the land.

To stay in a heritage hotel is to participate in an act of cultural meditation. It’s a choice to step out of the frantic pace of modern life and into a building that’s seen the rise and fall of empires. At Heritasian, we believe that to truly appreciate these stays, you must understand the architectural “dialects” they speak. To “read” the building is to understand the history of the person who built it, the climate that shaped it, and the culture that preserved it.

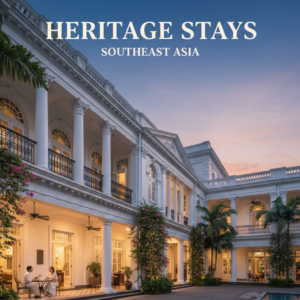

The Seats of Power: Tropical Neoclassicism

If the colonial era had a “brand,” it was Tropical Neoclassicism. This is the architectural language of the European empires—British, French, and Dutch—translated into an equatorial context. When you walk into a hotel like The Strand in Yangon or The Majestic in Kuala Lumpur, you’re entering a space designed specifically to project stability, authority, and permanence.

The Palladian Blueprint

At its core, this style is a revival of classical Greek and Roman traditions filtered through the lens of the 16th-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio. The hallmarks are unmistakable: perfect symmetry, grand pediments, and massive columns (Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian).

The Science of the “Grand Gesture”

Colonial architects realised that a stone temple would be a furnace in the humidity of Singapore. They had to “open up” the form, leading to the creation of the Veranda-centric mansion. By surrounding the core rooms with deep, shaded galleries, they created a thermal buffer zone.

The Sensory Signature: Horizontal Silence

In the Governor’s Mansion, the acoustics are horizontal and hushed. The massive scale of the rooms and the thickness of the masonry walls create a “reverent silence,” where footsteps on a checkerboard marble floor echo like a heartbeat. The scent is often defined by polished marble, cold lime plaster, and the faint, sweet trail of jasmine drifting in from the veranda.

Regional Rivalries: The Aesthetic of Empire

While the challenges of the heat were universal, the European powers solved them with different aesthetic “brands.”

The Legends: The Grand Dames

The “Grand Dames” are the matriarchs of hospitality. These are the “Palace” hotels built during the golden age of steamship travel—think Raffles Singapore or the Metropole Hanoi.

The Service of Memory

The Grand Dames are often accused of being “stiff,” but the anecdotes of their survival are deeply human. There is a famous story from The Strand in Yangon during its long years of isolation. The staff, many of whom had worked there for decades, continued to polish the brass and starch the linens with the same rigour as they had in the 1920s, even when there were no guests to see it. When you stay in a Grand Dame today, you are paying for the “institutional memory” of a staff that views itself as the curators of a museum.

The Mystery of Shanghai Plaster

If you look closely at the exterior of many 1920s Art Deco heritage buildings in Singapore or KL, you’ll notice a sparkling finish. This is Shanghai Plaster. Anorak travellers often mistake this for simple concrete, but it is actually a sophisticated mix of crushed marble, granite, and glass. It was the “luxury finish” of the early 20th century. Touching it is like touching a piece of history that refused to fade—a tactile connection to the craftsmen who migrated across the South China Sea.

The Science of the “Breathing” Wall

A major detail often missed is Madras Chunam—a traditional lime plaster made of lime, sand, egg whites, and jaggery. Unlike modern cement, which “chokes” a building, lime plaster is porous. It allows moisture to travel through the walls and evaporate. When you stay in a properly restored Heritage property, you are breathing air that has been naturally filtered through lime and stone.

The Cultural Synthesis: Straits Eclectic

Emerging in the mid-19th century throughout the Straits Settlements of Penang, Melaka, and Singapore, the Straits Eclectic style represents a unique historical moment. It is the visual manifestation of the Peranakan (Straits Chinese) heart—a place where Chinese floor plans met Victorian European ornament.

The Anatomy of the Synthesis

While the facade might feature Corinthian pilasters and Venetian shutters, the internal logic is strictly dictated by the Chinese courtyard house. These buildings are typically narrow and deep, a result of colonial land taxes based on street frontage.

The Living Internal Lung

The heart of this style is the Chim Chee (Air Well). This internal courtyard allows the tropical sun to illuminate the interior and permits rain to fall directly into the house. In the philosophy of Feng Shui, water represents wealth; to have the rain fall into the centre of your home is to literally welcome prosperity into your life.

The Sensory Signature: Participating in the Storm

In a heritage house with an open-air well, you participate in the storm. You hear the first fat drops hitting the terracotta tiles, the smell of wet stone rising from the floor, and the sudden drop in temperature as the house begins to “inhale” the cool air. It’s a moment of pure, unadulterated presence—a reminder that these buildings were designed to be part of the weather, not a defence against it.

The Urban Pulse: The Shophouse Hotel

If the Governor’s Mansion was the seat of power, the Shophouse was the engine of the city. Originally designed as “live-work” spaces for the merchant class, these buildings define the streetscapes of historic Asia.

The Merchant’s Legacy

The defining feature of the Shophouse is the Kaki Lima (Five-Foot Way) – a covered walkway mandated by colonial law to protect pedestrians from sun and rain. Today, staying in a shophouse hotel offers an “urban intimacy.” These stays are characterised by their verticality – steep timber stairs, high-perched windows, and a direct connection to the street life outside.

The “Anorak” Fact: The Window Tax Myth

Many believe the narrowness of shophouses was purely due to taxes, but it was also a matter of structural limits. Without steel beams, the width of a room was limited by the length of a single timber log available in the 19th century. This forced the “long-house” evolution that defines the urban Asian aesthetic.

The Indigenous Spirit: Vernacular Teak

While the Governors and Merchants were busy importing European ideals, a parallel world of luxury existed that was entirely indigenous. The vernacular mansions of Southeast Asia – specifically the grand teak mansions of Northern Thailand – represent a profound understanding of the landscape.

The Science of the Stilt

Raised on heavy timber stilts, these buildings were designed to survive seasonal rhythms. Lifting the living quarters allows air to circulate underneath the floorboards, pulling heat away. The steep, dramatic roofs shed torrential rain instantly and create a massive internal “void” for hot air to gather.

The Sensory Signature: The Sound of the Forest

In a 100-year-old teak mansion, the house “talks” to you. It’s the rhythmic clack-clack of floorboards that have slightly bowed over a century, and the smell of rain-dampened wood that hits you before the storm even arrives. It is a stay that grounds you, reminding you that true luxury is finding a harmonious way to live within nature.

The Adaptive Reuse Conflict: Luxury vs. Authenticity

The most difficult task for any heritage hotel is the “Bathroom Problem.” How do you install a 21st-century, high-pressure rainfall shower into a 19th-century timber floor without causing rot?

The gold-standard properties solve this through adaptive reuse – building “structures within structures” where modern plumbing and AC are hidden behind period-accurate wood lattices. This tension between modern comfort and historical integrity is exactly why heritage travel is a form of mindfulness; it asks the guest to accept the slight creak of a floorboard as a fair trade for an experience that cannot be duplicated.

Conclusion: Becoming a Guardian of History

In an era of generic luxury, choosing a heritage stay is a quiet act of rebellion. It is a decision to slow down, to breathe the same air as the merchants and governors of the past, and to acknowledge that the buildings we inhabit shape the stories we tell. Every time you book a heritage room, you are funding the survival of the craft—the tiles, the carvings, and the history.

In these buildings, the walls do talk. Your stay is simply the next chapter in their story.

Join the Heritage Dispatch

Our journey through the architectural DNA of Southeast Asia is just beginning. Join the Heritasian circle to receive our curated deep dives into the region’s most legendary properties.