Stand on the shores of Langkawi today, and travellers can gaze upon a landscape defined by deep time. The island archipelago, a designated UNESCO Global Geopark, has mountains and rock formations over 550 million years old. This geological permanence, however, stands in sharp contrast to Langkawi’s history-and the short, violent struggle of its inhabitants—a history stained by conquest and dominated for centuries by a single, tragic injustice – the legend of Mahsuri.

This foundational sorrow is known throughout the Straits of Malacca. Legend tells of the beautiful maiden, Mahsuri, unjustly executed for alleged adultery in the late 18th century. Her execution sealed her infamous prophecy with pure white blood, cursing Langkawi to misfortune for seven generations. The island’s journey to modern success involved military devastation, political negotiation, and an eventual triumph over that curse.

Langkawi History: The Catastrophe of 1821

The true test of Langkawi’s legend arrived not as a creeping famine, but as a sudden, shattering military disaster. The Kedah Sultanate’s diplomatic failure decided Langkawi’s fate. The British Empire and the Kingdom of Siam trapped the ruler between their expansionist interests.

The Gathering Storm of 1821: An Act of Defiance

The crisis reached its peak when Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Halim Shah II made a fateful choice. He refused to send the customary tribute to the court of Siam. It was an act of sovereignty, but in the reality of those times, it was a declaration of war. Langkawi, positioned between the two great powers, was to become the sacrificial lamb.

Phraya Thaninthon’s Treachery: The Invasion

In late 1821, the full might of Siam descended. Phraya Thaninthon, the Governor of Ligor (Nakhon Si Thammarat), spearheaded the invasion ruthlessly and effectively.

The Siamese used a masterful military deception: boats seemingly buying supplies in Kedah quickly became an armada. The capital fell swiftly, forcing the Sultan to flee to British Penang. His pleas for aid went unanswered—a bitter lesson in colonial expediency that sealed Langkawi’s isolation.

The Flames of Defiance: Padang Matsirat

With the mainland secured, the Siamese forces turned their attention to the archipelago, determined to extinguish all pockets of resistance. The local defence was hopeless against the overwhelming numbers. And chose a terrible form of defiance over surrender: a desperate scorched-earth policy.

This sacrifice culminated in the most famous anecdote of the invasion. The torching of the immense communal rice stores at Padang Matsirat. To deny the invaders food, the islanders intentionally set fire to the stores of grain, the literal lifeline of the population.

The smell of burning rice must have hung heavy in the air for days. It was an act of heart-wrenching desperation: self-inflicted starvation to spite the aggressor.

Even today, heavy rain reveals blackened rice grains in the soil, a physical relic of that sacrifice. The Siamese Invasion of 1821 was the mechanism that turned the seven-generation curse into a devastating historical reality.

The March of the Captives

The aftermath was a humanitarian disaster that cemented the local belief in the curse. The Siamese occupation efficiently and brutally rounded up thousands of islanders who couldn’t flee and marched them north, condemning them to slavery in Siam. This shattered Langkawi’s economy, scattered the remaining population, and left a broken, desolate shell ripe for exploitation.

Langkawi History of Pirate and Colonial Bargains (1842–1957)

The trauma of the invasion created a political vacuum that lasted over a century. The desolation left by the Siamese ensured that Langkawi wouldn’t recover quickly. And so it turned into a magnet for maritime outlaws.

Pirate Haven of the Straits

Langkawi’s hidden coves and deep channels made the 99-island archipelago a perfect pirate base. These outlaws mercilessly preyed on the lucrative trade moving through the Straits of Malacca. Pirates were so notorious that European ships sailed around Langkawi to avoid raids and unpredictable weather. This fear isolated the island from global trade and investment, leading to chronic poverty for generations.

The Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909: A Cynical Exchange

The fate of Langkawi Island was ultimately decided in the halls of power, not on its shores. This occurred with the signing of the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909.

This was a calculated geopolitical exchange. Great Britain, seeking to solidify its control over the Malay Peninsula, bartered with Siam. The treaty resulted in Siam giving up its claims over the four Northern Malay States. Great Britain secured Kedah (including Langkawi), Perlis, Kelantan, and Terengganu from Siam in exchange for concessions elsewhere.

For Langkawi, this transfer was merely a shift in ownership from one distant master to another. Kedah became an Unfederated Malay State (UMS). While this meant less direct colonial control, it had a major disadvantage. The state received less financial investment than the centrally governed Federated Malay States.

British policy prioritised the tin and rubber industries of the central states, leaving Langkawi a marginal outpost. While the British poured capital and infrastructure into Penang—their administrative and commercial hub just a short sail away—Langkawi was left to languish, its economy barely rising above subsistence.

This neglect meant that even by the outbreak of World War II, Langkawi was profoundly underdeveloped. Its vulnerability was underscored again when the Japanese ceded administrative control of the northern states back to their ally, Thailand, in 1943. For a short period, the Siamese flag flew once more over the land.

The Political Cure: A Natural Heritage Awakens

The island finally gained sovereignty in 1957, but its economic woes lingered. The cycle of misfortune, however, was about to be broken. A decision to leverage its natural wonder, coinciding with the folkloric generational curse drawing to a close.

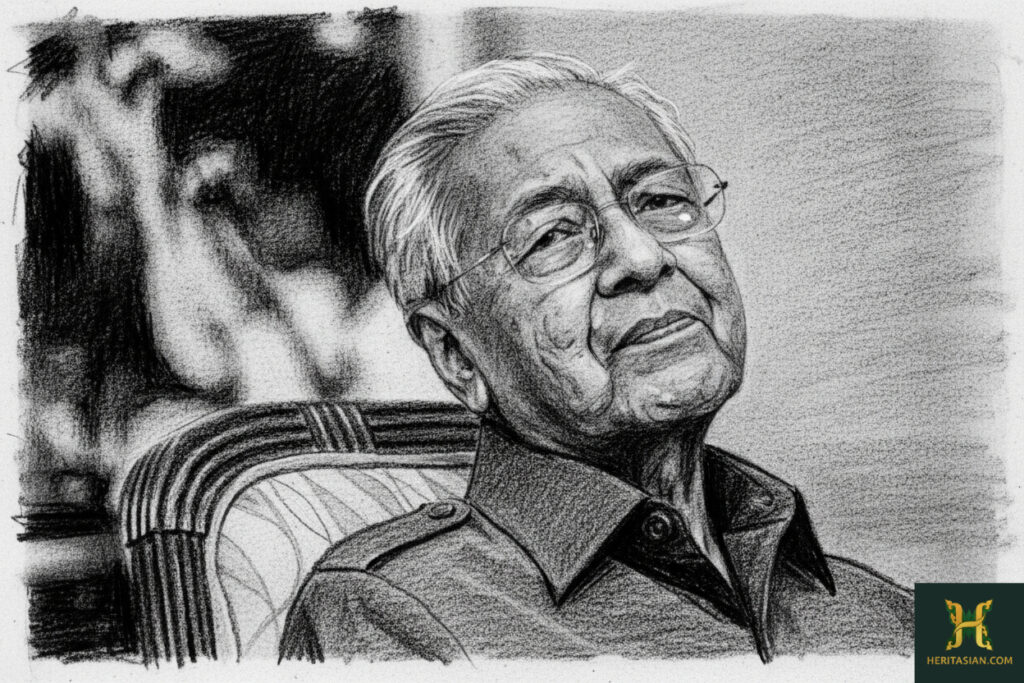

The architect of this was Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, a local son of Kedah. His famous economic intervention was the declaration of Duty-Free Status on January 1, 1987. However, his long-term vision was broader. He planned to anchor the island’s future not just in commerce, but in its unparalleled environment.

This vision transformed Langkawi from a forgotten outpost into a global ecotourism destination.

Recognising the mountains and mangroves as its most valuable assets, Langkawi was designated a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2007. This political decision tied the island’s prosperity directly to preserving its natural heritage tourism.

Gunung Raya

The highest mountain on Langkawi Island, Malaysia, is a prominent feature of the island’s landscape, both ecologically and mythologically. Folklore deeply roots the name “Gunung Raya,” which means “Great Mountain,” in Langkawi’s cultural history.

Legend has it that Gunung Raya is the petrified form of a giant named Mat Raya. He fought a legendary battle against the giant Mat Cincang (now Gunung Machinchang) at their children’s wedding. A local sage ended the destructive fight. He did this by cursing and transforming all three giants into the mountains of Langkawi. The peacemaker, Mat Sawar, was included in the curse.

Facts and Features

Elevation: It stands at an impressive 881 meters (2,890 feet) above sea level, making it visible from nearly every part of the island.

Geological Significance: Granite primarily composes the mountain, making it the youngest rock formation in Langkawi at 200–220 million years old. Its weathering creates the unique mineral deposits found on beaches like Pantai Pasir Hitam (Black Sand Beach).

Biodiversity: Gunung Raya is covered in dense tropical rainforest, serving as a vital “green lung” for the island. It’s a sanctuary for a diverse array of wildlife, including Great Hornbills (the largest hornbill species in Malaysia), leaf monkeys, flying foxes, and several newly discovered species of reptiles and amphibians.

Accessibility: The summit can be reached in two main ways:

- A long, winding, paved road allows visitors to drive directly to the summit area.

- The challenging Tangga Helang Seribu Kenangan (Thousand Memories Eagle Stairs) is a long staircase trek of over 4,000 steps that takes hikers directly up the mountainside.

Views: From the peak, visitors are rewarded with panoramic, 360-degree views of the entire island, the surrounding Andaman Sea, and often, views stretching to the islands of Thailand on a clear day.

Pulau Dayang Bunting

It is often called Pregnant Maiden Island. It is the second-largest island in the Langkawi archipelago. The island is renowned for its distinct geographical silhouette. It also holds a legendary freshwater lake. It’s a major stop on most Langkawi island-hopping tours.

The island’s most famous attraction is a freshwater lake located in its centre, separated from the sea by only a thin wall of limestone.

The lake is steeped in local folklore and is believed to possess mystical powers related to fertility. This powerful combination of supernatural belief and striking natural beauty makes Pulau Dayang Bunting a celebrated cultural and natural landmark in Langkawi.

The Story: A celestial princess named Mambang Sari fell in love with a prince named Mat Teja. They married and had a child who, tragically, died just seven days after birth. Heartbroken, Mambang Sari laid the baby’s body in the lake before returning to her heavenly abode.

The Blessing: Before she left, the princess blessed the lake’s waters, endowing them with the power to cure infertility. Both locals and tourists believe that the lake’s water grants the miracle of a child to barren women.

Geology: Rainwater filled this natural sinkhole, known as a doline, after the roof of an ancient limestone cave collapsed. The island itself is part of the Dayang Bunting Marble Geoforest Park, recognised for its 290-million-year-old marble rock formations.

Activities: Visitors reach the lake via a short, uphill jungle trek. Once there, they can enjoy swimming (life jackets are mandatory due to the low buoyancy of freshwater), kayaking, or paddle boating on the tranquil, cool waters.

Pantai Cenang

It’s the most famous beach on Langkawi Island, known for being the island’s primary tourist hub. It’s an approximately 2-kilometer-long stretch of white sand that perfectly blends relaxation, adventure, and nightlife.

It is also the most developed area on Langkawi’s west coast, offering a centralised location for accommodation, dining, and activities.

Water Sports and Relaxation (Daytime)

The beach itself is a hive of activity during the day, offering clear waters for swimming and sunbathing, as well as easy access to a full range of water sports.

Adventure: You can easily find operators offering jet-skiing (including popular island tours), parasailing, and banana boat rides.

Relaxation: The wide, soft sands are lined with palm trees and beach chairs/umbrellas, making it ideal for simply relaxing and enjoying the scenery

Dining, Shopping, and Nightlife (Evening)

As the sun sets, Pantai Cenang transforms into Langkawi’s social centre.

Sunset Views: It is one of the best spots on the island to watch the stunning tropical sunsets over the Andaman Sea.

Nightlife: Beach bars and cafes set out beanbag chairs on the sand, offering cocktails, live music, and sometimes fire shows (often performed for tips).

Duty-Free Shopping: Numerous shops line Jalan Pantai Cenang, including duty-free outlets that offer tax-free chocolates, liquor, and perfumes.

Cuisine: The area has a diverse food scene, from affordable local street food and seafood restaurants to international cuisine (Thai, Mexican, Italian).

Pantai Cenang is a short walk or drive from several other major attractions:

Underwater World Langkawi: One of Southeast Asia’s largest aquariums, featuring a walk-through tunnel and specialised sections for marine and freshwater life, including penguins.

Laman Padi Langkawi: A rice garden and museum complex that offers insights into the history and processes of rice cultivation in Malaysia.

Temoyong Night Market: A lively weekly market (typically every Thursday) offering local food, snacks, and inexpensive goods.

Langkawi History: Scars as Assets, The Future as Green

The historical adversity of Langkawi today serves not as a burden but as a compelling layer of its identity. The island found its symbolic closure when Mahsuri’s seventh-generation descendant, Wan Aishah, was traced and visited, marking the redemption of the past.

The Curse is Truly Lifted

You can witness its end by exploring the green sanctuary that remains: kayaking through silent mangrove forests, climbing the ancient rock faces of Machinchang mountain, or simply watching the sea eagles soar over the coves that once hid pirates. Every preserved piece of nature reminds us of the island’s ultimate triumph over historical neglect.

Langkawi is now more than a duty-free haven; it is a living monument to resilience, where the geological foundation, laid half a billion years ago, now cradles a hard-won peace. Come, then, not just to see the landscape, but to feel the echoes of history settle into the profound silence of its ancient, restored green heart.

Langkawi History FAQs

Who was Mahsuri, and what is the significance of her legend to Langkawi?

Mahsuri was a beautiful maiden in the late 18th century who was unjustly executed for alleged adultery, and her dying curse, marked by the flow of white blood, doomed the island to misfortune for seven generations until her descendant was traced, lifting the spell.

What was the Catastrophe of 1821, and what caused it?

The “Catastrophe of 1821” refers to the devastating Siamese invasion of Kedah and Langkawi, which was sparked by the Kedah Sultanate’s refusal to send the customary bunga mas (golden flower tribute) to the Siamese court.

How did the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 affect Langkawi’s development?

A: The Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 resulted in Great Britain taking control of Langkawi (as part of Kedah) from Siam, but the subsequent designation as an Unfederated Malay State (UMS) meant the island suffered from chronic underdevelopment and low colonial investment.

What is the legendary connection between Gunung Raya and Langkawi’s folklore?

Gunung Raya is the island’s highest mountain. Folklore says it is the petrified form of a giant. This giant was named Mat Raya. He was cursed and turned to stone after a legendary battle. He fought against another giant, Mat Cincang. Mat Cincang became the island’s second-highest peak.

Who was the Architect of Renewal, and what was his major contribution to Langkawi’s economy?

The Architect of Renewal for modern Langkawi was Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, a local son of Kedah, whose most significant economic contribution was declaring the island a Duty-Free Zone on January 1, 1987.