The world’s great journeys are rarely confined to a single timeline. In Southeast Asia, history is not a dusty archive. It lives in the streets, in the aromas, and in the very walls where you sleep. A crucial choice awaits the discerning traveller. Do you surrender to the epic scale of the Colonial Grand Dame? Or do you step into the intimate narrative of the shophouse boutique? This choice defines your entire encounter with a city, and it is the central question of this guide: shophouse boutique vs colonial grand dame.

The Core Question: Choosing Your History

This is a decision about more than just a hotel room. It sets the pace of your days. The difference is profound. The Grand Dame offers an opulent window into a bygone empire. You look out at the world from a place of lofty prestige. Conversely, the Shophouse stay pulls you in. It immerses you instantly into the granular, buzzing rhythm of a local neighbourhood. Both choices preserve architectural marvels. Yet, the stories they tell are radically different. One speaks of marble halls and globe-trotting writers—the other whispers of family trades and spice routes. We delve into these two defining styles.

The Grand Dame: An Empire’s Endlessly Elegant Stage

The Colonial Grand Dame is an enduring monument to external power. These hotels were not built to blend in; they were designed to dominate the tropical landscape and offer a perfect, civilised retreat.

Architecture of Aspiration and Scale

The scale is the first shock. These buildings possess immense, sweeping facades, often in Neo-Classical, French Colonial, or Victorian styles. Think of the towering ceilings and deep, sheltered verandahs of the Raffles Hotel, Singapore. Architects employed volume to defeat the heat. They prioritised high ceilings and enormous public rooms for social spectacle. Vast quantities of Italian marble, English tile, and French wrought iron were imported to convey permanence and European sophistication. The design was intended to dwarf the guest. It conveyed power and aloofness.

The quintessential example remains the Raffles Hotel, Singapore. It is more than a hotel; it is a national monument, gazetted in 1987. Anecdotes abound within its walls. An escaped circus tiger was once cornered beneath the Bar & Billiard Room in 1902. Literary giants like Rudyard Kipling and Somerset Maugham found inspiration on its deep verandahs. The Raffles Hotel, Singapore, began in 1887 as a 10-room beach house. It evolved into a complex of neo-Renaissance architecture. Every detail asserts its power and pedigree.

Service, Setting, and Social Ritual

The service model is equally grand. It is formal, precise, and often involves dedicated butler service. Guests expect high tea in a hushed parlour. The location is strategic: prime seafronts, riverbanks, or vast central city plots. Their purpose was insulation. They created a serene, manicured bubble, separating the visiting aristocracy from the local bustle. You are a guest observing the city.

Guests expect their every need to be met via swift room service. They dine in hushed, formal dining rooms. The Grand Dame maintains an endlessly elegant distance from the daily toil of the city. A key part of its legend is its most famous export: the Singapore Sling. Bartender Ngiam Tong Boon invented the Singapore Sling at the Long Bar in the Raffles Hotel in 1915. He cleverly designed the pink, gin-based cocktail to look like a socially acceptable fruit juice for ladies. This invention captures the sophisticated, yet formally rigid, atmosphere of the old Singapore elite. The Grand Dame remains endlessly elegant because its luxury is a statement of historical continuity.

The Shophouse Boutique: A Conservation Gem of Local Life

The Shophouse Boutique is a celebration of the vernacular. This genre is a functional art form, created by the Chinese immigrant merchant class. It is architecture born of necessity, not conquest.

Architecture of Adaptation and Fusion

The Shophouse scale is intimate. It is narrow, deep, and built in contiguous rows, adhering to the long, thin plots often taxed by street frontage. They are typically found in UNESCO-listed urban enclaves. The facades are vibrant mixtures: Chinese ceramic tiles, Malay timber accents, and European baroque plasterwork.

The architectural features convey a sense of practicality and fusion. A key element is the mandatory five-foot way, a sheltered walkway stipulated by Sir Stamford Raffles’ 1822 town plan for old Singapore. This ensures pedestrians are protected from the sun and rain. Today, a carefully restored, pristine Peranakan shophouse is a prized architectural achievement. These buildings are celebrated as a conservation gem. Property groups, including those under the Far East Hospitality umbrella, are key players in transforming these complex spaces. The restoration prioritises the internal airwell, which funnels light and air deep into the long building—a crucial passive cooling technology.

Immediate, Neighbourhood Immersion

The shophouse boutique rejects the Grand Dame’s insulation. It embraces the street. Staying in a Peranakan shophouse means stepping directly onto the street. Your luxury is not a bubble, but a filter. This is a conservation gem of residential luxury.

The atmosphere is quiet luxury, but with an edge of local, authentic texture. Your defining feature is the street life. You wake up inside a working, living neighbourhood. The business model, often supported by Far East Hospitality, depends on guests valuing this immediate access.

Architectural Deep Dive: Materiality and Climatic Control

The structural differences between the two forms reveal their contrasting priorities and economic histories.

Grand Dame Construction: Imported Heaviness

Colonial hotels were built to be unyielding. They used thick, heavy construction—load-bearing walls of brick and stone, rendered in stucco or chunam (lime plaster). The roofs were pitched, often tiled, with deep eaves to shade the windows. The materials were chosen for their European familiarity and perceived permanence: heavy teak for flooring, vast quantities of marble for public areas, and glass for windows. Airflow relied on immense volume and large windows, supplemented by ceiling fans. These structures were expensive to build and required huge initial capital—a mark of imperial investment.

Shophouse Technology: Local Ingenuity

Shophouses were built using local or easily imported materials by Chinese craftsmen. The architecture is modular and thin-walled (shared party walls). Construction relied on timber beams and masonry. The shophouse’s genius lies in its climatic adaptation:

- The Airwell: This inner courtyard ensures cross-ventilation, drawing hot air up and out, acting as a passive chimney.

- Peranakan Tiles: Highly ornate ceramic tiles on facades served a dual purpose: decoration and a durable, heat-resistant cladding.

- Jalousie Windows and Shutters: These allowed light and air in while maintaining privacy and shading the interior—a sophisticated response to the tropical sun. The Shophouse is an evolved solution to dense urban life in the equatorial zone, a true fusion of Chinese geometry and Malay climate consciousness.

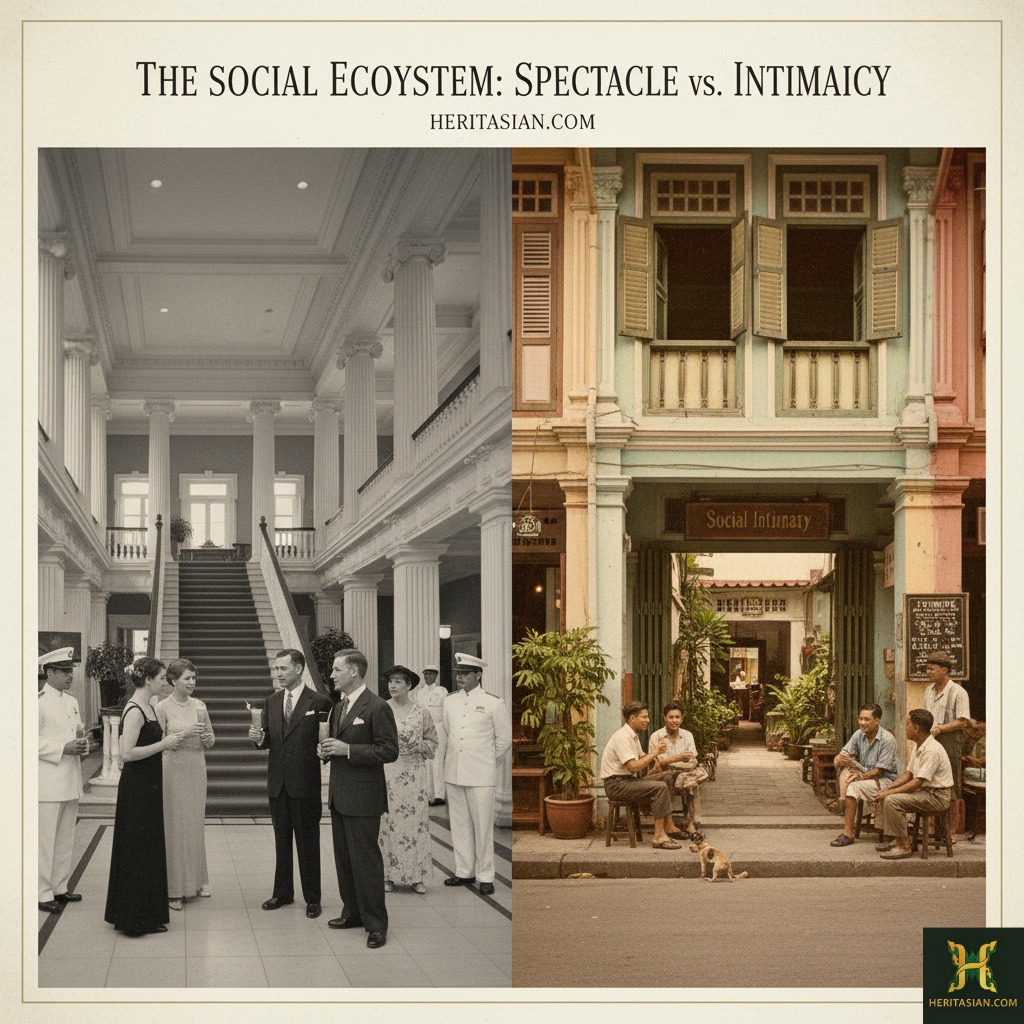

The Social Ecosystem: Spectacle vs. Privacy

The social history of each structure dictates the interaction you have as a guest.

The Grand Dame was a social theatre. The wide lobby, the ballroom, and the dining halls were stages for the colonial hierarchy. The staff were part of the spectacle, trained in formal European service to cater to the guests’ complete isolation from local life. The invention of the Singapore Sling was a perfect social lubricant for this insulated world. Service is delivered at a distance.

The Shophouse Boutique operates on a level of social intimacy. The staff often include residents, providing an immediate, personal conduit to the old neighbourhood. There is no grand lobby spectacle. Public spaces are often small, repurposed courtyards or lounges. Your interaction is with the street life. This style of stay demands engagement—you share the five-foot way with local vendors and residents. People consider the noise and smell of the adjacent hawker centre amenities, not intrusions.

Showcase: Malaysia’s Defining Shophouse Stays

The best examples of the Shophouse Boutique demonstrate true reverence for vernacular architecture. These hotels are not simply converted buildings; they’re curated historical experiences found in Malaysia’s premier heritage cities. They represent the ultimate triumph of the local design narrative, far removed from the high tea rituals of the colonial era.

1. Jawi Peranakan Mansion, Georgetown

This is a remarkable example of Anglo-Indian and Peranakan fusion. The Jawi Peranakan (locally born Muslims of mixed Indian and Malay ancestry) originally built it in the 1890s. Unlike the single narrow shophouse, a block of four terraced houses composes the mansion, which creates a grand, self-contained compound. The restoration showcases exquisite detail, particularly the large central courtyard and the distinctive chunam plasterwork. The history here is one of cultural blending, reflecting Georgetown’s complex society, far from the purely European narrative. It is a lavish, multi-generational home converted into an opulent sanctuary. The rooms are immense, reflecting the family’s wealth, but the atmosphere remains distinctly private and residential. It is a prized conservation gem.

2. Hotel Puri Melaka, Malacca

Hotel Puri is a landmark on Malacca’s famous Jonker Street. The building itself was once the ancestral home of a prominent Peranakan family. Its core is a magnificently preserved structure reflecting the architectural style of the 18th to 19th centuries. The central courtyard here is famous, dominated by tropical plants and open to the equatorial sky—a true airwell in action. The history is intimate: it speaks of the matriarchs, the long tables, and the specific, highly detailed furniture of the Baba Nyonya culture. Staying here is like being a guest in a grand family’s life in the old neighbourhood, not a customer in a grand resort. The original teak wood beams and intricately carved folding doors remain intact, demonstrating the commitment to conservation. This is a profound connection to local history.

Seven Terraces, Georgetown (Penang)

This hotel is a masterclass in the restoration of a row of Late Straits Eclectic shophouses. The property is a redevelopment of the original Lee Kongsi clan association building, circa 1893. It consists of seven interconnected, contiguous shophouses, giving the hotel its grand scale and name. The focus is squarely on the opulent Peranakan Chinese material culture. The interiors feature spectacular air-wells that draw in light and air, traditional patterned floor tiles, and intricate Peranakan carvings and artwork. The conservation effort here has perfectly preserved the structural Longhouse typology, which is deep and narrow with multiple courtyards, demonstrating the ingenious adaptation of housing to the tropical climate. Staying at Seven Terraces offers an immersion into the historical splendour and aesthetic detail of Penang’s wealthy Baba Nyonya merchants.

The Value Proposition: Price, Perspective, and Preservation

Both styles represent a premium product, but their value metrics diverge sharply.

The Colonial Grand Dame delivers value through tangible assets. This means sheer scale, immense service ratios, and globally branded luxury. This experience comes at a significant price point, reflecting the cost of maintaining such vast, formal institutions. The Sarkies Brothers, who founded the Raffles Hotel, were masters of this high-volume, high-prestige hospitality. You pay for the guaranteed, immaculate bubble.

The shophouse hotel in Southeast Asia, often a conservation gem, delivers value through perspective and curation. Its price reflects bespoke, intimate design, hyper-local authenticity, and architectural preservation. The value is found in the detail: the discovery of a quiet reading room carved out of an airwell, the immediate access to the best street food, and the feeling of living inside history. The approach favoured by Far East Hospitality in their heritage stays emphasises this curated immersion. You are paying for a deeper, more immediate cultural lens, which, for many modern travellers, surpasses the value of traditional luxury.

The Legacy of Conservation: A Challenge of Heritage

Both heritage forms present unique challenges for modern conservationists and hoteliers.

The Colonial Grand Dame requires massive capital investment to maintain its scale. The challenges include preserving enormous timber structures, restoring miles of stucco and chunam plasterwork, and updating plumbing and electrical systems without compromising the historical fabric. The rediscovery and restoration of the bomb shelter at the Sofitel Legend Metropole Hanoi, built in 1964, is a powerful anecdote of this dedication—preserving wartime history within a luxury setting.

The Shophouse Boutique faces challenges of density and context. Conservation efforts focus on maintaining the integrity of the whole row, not just the single unit. Preserving the five-foot way and the integrity of the party walls while providing modern soundproofing and air conditioning is a delicate technical dance. The successful restoration of a magic pristine Peranakan shophouse is a victory for urban heritage, preventing demolition and ensuring the continuation of the old neighbourhood’s unique character.

The Definitive Choice: Grandeur or Grace

The Colonial Grand Dame delivers the lofty narrative. Choose this if you seek the high theatre of empire, where every service bell echoes with the names of storied travellers. The Raffles Hotel remains the perfect example of this immense scale. This is where you retire to a Singapore Sling after a day of curated sightseeing.

The Shophouse Boutique offers an intimate conversation. Select this to step into the immediate, bustling story of the merchant. Feel the city’s pulse through the soles of your feet. This is where you grab a coffee from the hawker centre before starting your day.

The definitive choice is not about luxury—it is about the historical distance you wish to keep. One allows you to observe history. The other allows you to live inside it.

Shophouse Chic Vs Colonial Gradeur FAQs

What are the key architectural differences between “Shophouse Chic” and “Colonial Grandeur” heritage hotels?

Scale (intimate vs. vast), building type (narrow townhouse vs. grand mansion/palace), and design focus (local vernacular vs. European style).

Where in Southeast Asia are you most likely to find iconic Colonial Grandeur hotels?

Major capital cities with significant colonial history (e.g., Hanoi, Yangon, Singapore, Penang, Bangkok) and large, riverside, or prominent land plots.

Which type of traveller is better suited for a Shophouse Chic stay?

Travellers seeking a highly localised, intimate, boutique experience with easy access to street life and local food.

What is the historical significance of the buildings used for Shophouse Chic hotels?

They originated as mixed-use, two- or three-story commercial-residential buildings built by local traders, often reflecting a blend of Chinese, Malay, and European influences (e.g., Sino-Portuguese style).

Is one style generally more expensive or luxurious than the other?

Colonial Grandeur is typically associated with a higher price point and formal luxury, while Shophouse Chic offers boutique luxury that is often more design-focused and moderately priced.